One of the nicer experiences I had while writing

The Most Remarkable Woman in England was having the chance to personally get to know -- first via email then in person -- a few of Beatrice Pace's descendants. I found them quite by chance via the Internet (how does anyone find anything these days otherwise?) when one of her...wait, let me get this right...

great-granddaughters had made an offhand comment about her family history at a web forum on a completely different topic (a popular television game show, as I recall).

This is what led me to writing her.

(After I became the member of an internet forum regarding a show I'd never at that point watched. My devotion to historical research, clearly, knows no bounds.)

In any case, emails were passed along and exchanged, and I was soon communicating with one of Beatrice's grandsons. After years of research via newspapers and official files, it was quite an experience to finally be in touch with someone who had personally known the main person profiled in my book. As '

Gran'. (Beatrice had a long life after her trial.)

A couple of trips of mine to Gloucestershire and the Forest of Dean followed, and I am very grateful, both for the information I received and the hospitality I enjoyed there.

Later, I corresponded with another grandson who provided me with a few of the pictures used in the book.

As to the information about Beatrice's post-trial life, you'll have to, as they say, read the book.

However, I thought I would share an aspect of how it came to be written.

When I first decided to get in touch, I had, I must admit, some qualms. In fact I debated with myself for some weeks before making initial contact. Of course, I wanted to find any relevant information for my book: most of all, I was aiming at filling in the story of what happened to Beatrice Pace

after she disappeared from the headlines...and therefore from the historical record.

On the other hand, I wasn't quite sure what reaction to expect.

I mean: someone shows up out of the blue and says he's writing a book about your grandmother who was accused of murder? How would

you react?

I am pleased to say that the family members I have dealt with have been nothing but friendly and have all been very supportive of the project, providing me with helpful details about the later life of the 'Tragic Widow of Coleford', as she was known in the late 1920s. In return, I am pleased to have been able to fill in many details for them about a striking aspect of their own family history.

That was nice enough.

However, a couple of weeks ago this story took another twist.

While we were on holiday, I was contacted by another of Beatrice's descendants: the grandson of a different one of her children than the people I had to this point spoken to. He had heard rumours of this book online last year and then found this blog.

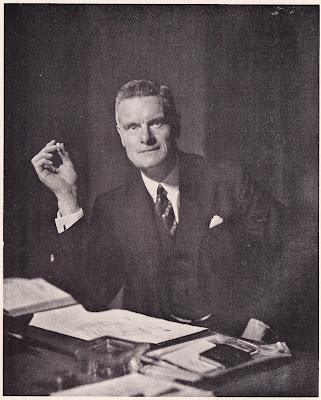

Very kindly enough he sent me a few family photos that I hadn't yet seen, and, even more kindly, he said I could share them here on the blog.

Although I have very few details about either of them, I estimate that they're both from the mid-to-late 1930s. The first is of Beatrice with her youngest daughter 'Jean' (actually Isobel Jean). Jean, sadly, was a sickly girl and died during the Second World War aged 14. She had, as I describe in the book, been a prominent focus of coverage of the Pace case in 1928 and was frequently mentioned in letters Beatrice received from her supporters and admirers. (One of the aspects of the case that I consider was the way the public responded to press reporting of it.)

Along with any information that I received through getting to know the family the experience very much helped to bring something home to me: that history is about real people. This may sound banal, but when you spend large amounts of time getting to know people through reading

documents (and even printed pictures) their reality becomes a bit abstract.

Speaking to people who had known Beatrice Pace personally -- had seen her, heard her voice, touched her -- certainly helped to give my own perspective on the case a new vividness.

One that I hope I have been able to impart.